Busy is not productive

A few years ago, I experienced the busiest period in my career so far. I was working full-time, going to school part-time, and working on a short-term assignment that required me to live in another country for a few months. I was also trying to maintain a social calendar and carve out quality time for family and friends.

After I graduated, I changed jobs. The time I had spent on researching a dissertation was now filled with travel and onboarding into a new company. Then, a few months later, the whole world shut down for COVID, and I was forced to reckon with the question of how I should be spending my time.

With the onset of the pandemic, I no longer had a commute. I wasn’t spending time in hallway conversations or rushing to meet friends for happy hours. I had enormous amounts of free time and no idea what to do with it. I felt constant guilt that I was wasting time and not being more productive.

I had become so conditioned to constant activity that I mistook busyness for productivity. It’s a trap many of us, and many companies, are still struggling with today. At the crux of the struggle is the fact that we do not have a good way to measure knowledge worker productivity.

Here’s the thing – it’s easy to quantify busyness. If you spend a day sending emails, submitting expense reports, and going to meetings, you can count the tasks you completed. If you spend the day engaged in deep work that leads to a product enhancement that eventually generates millions in profits, you can’t quantify the productiveness of that day immediately. In retrospect, it will be clear which day created more value for the business, but in the short term, it may feel like the administrative day was more productive.

And that’s the trap - when we mistake busyness for productivity, we don’t leave space for innovation. Without that space, we condemn ourselves to an unproductive cycle of doing for doing’s sake.

To break out of this cycle, we can focus on outcomes. What are we trying to accomplish? What ultimately will create value, and how can we prioritize the things that help us achieve the desired outcomes?

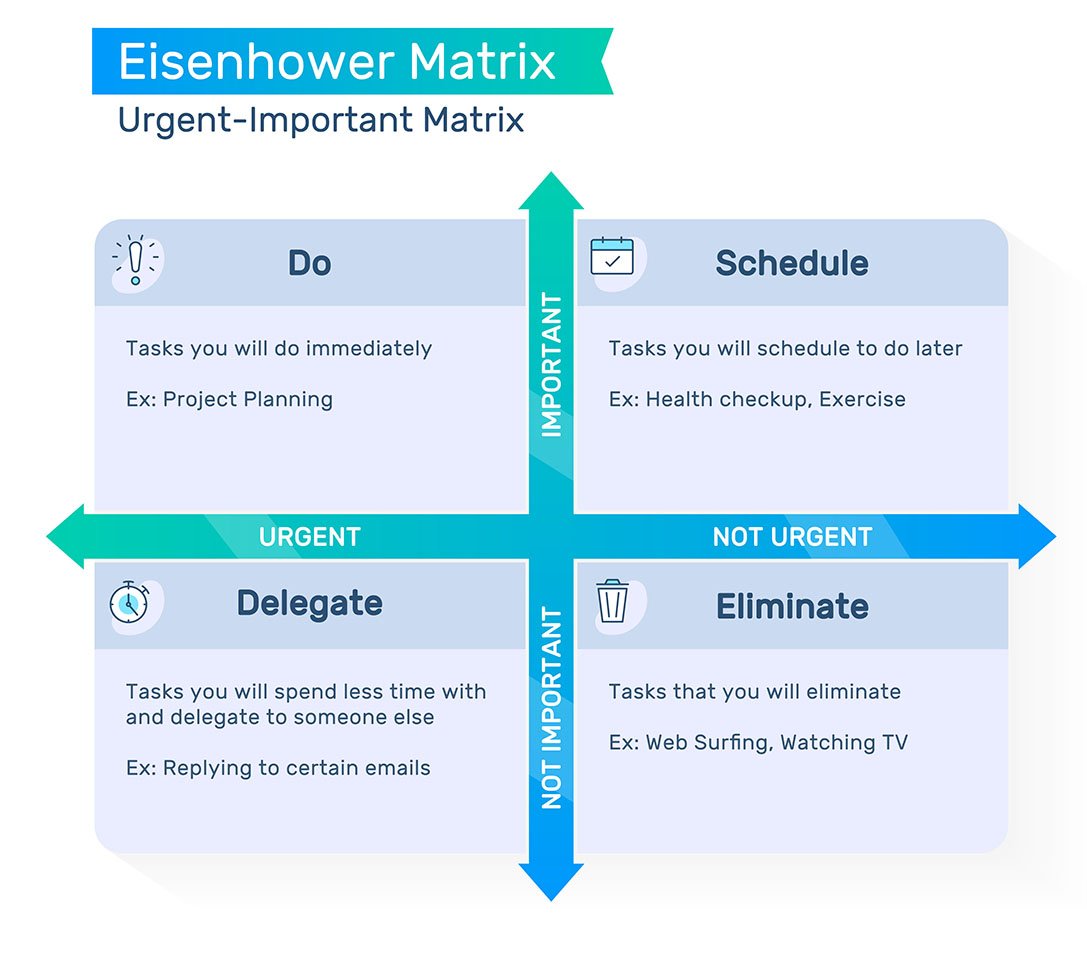

Personally, I use my inbox as a “to-do” list. If an email has a task associated with it, I mark it unread until I complete the task. Then, I file the email. Anything that doesn’t have a task associated with it, I read and file. The downside is that during really hectic times, email used to become my primary task, which was not productive. So, I started using the Eisenhower Matrix to focus only on urgent and important items.

I tagged emails as they came in – Priority, Schedule, Delegate, Eliminate. I handled Priority items first and set a reminder to handle the Schedule category. I would hand off Delegate items to colleagues, and I would ignore the Eliminate items.

When I did this, something amazing happened – the items in the Eliminate category tended to resolve themselves. Other people stepped in and answered the question or completed the task. I realized how much time I was spending doing things that were just not important for the outcomes I needed to achieve.

While the number of tasks I completed dropped, the quality of my outcomes rose. I was more focused. I was able to contribute in more strategic ways, and I felt more fulfilled. I finally had time for the deep work. I’m still not sure how to quantify that, but I’d love to hear how you measure productivity for knowledge workers. Share your thoughts in the One Question Poll here.